This post may contain affiliate links, including Amazon.com(and affiliate Sites/Stores.)Any One Can Shop from this blog.Using links to these sites means I may earn a small percentage from purchases made at no extra cost to you.

Hey Everyone!,

How To Unlock the Amazing Power

of Your Brain and Become a

Top Student

I was a mediocre K–12 student but graduated #1 in my medical school class. Here’s how I did it.

Carol Dweck’s research has proven that with a growth mindset, you can achieve way more than you ever dreamed. But being successful in school, particularly in university, is a complex undertaking. Most of us never come close to realizing our potential as students. I found a set of strategies and tactics to unlock the amazing abilities that all of our brains possess.

Do you think it’s possible to take an average student and teach him or her how to learn so that with a dose of grit and persistence, he or she can become the top student in the school? Well, that’s my story. And along my road to success, I discovered some effective study techniques based on cognitive psychology that have changed my life.

Let me start at the end of the story and then explain how I got to where I am today. I’m a 66-year-old retired physician. I practiced radiology for 30 years and retired from my medical career in 2014. Additionally, I’m a serial entrepreneur and co-founder of aytm.com and iDoRecall.com.

Let me start at the end of the story and then explain how I got to where I am today. I’m a 66-year-old retired physician. I practiced radiology for 30 years and retired from my medical career in 2014. Additionally, I’m a serial entrepreneur and co-founder of aytm.com and iDoRecall.com.

I graduated high school in 1970, finishing within the 50th percentile of my class. From grades K through 12, I struggled with learning. I was given a lot of after-school tutoring by my teachers during grade school. I was not aware of having any learning disabilities. I had above-average ability and always tested high on standardized exams, but I was never a good student, even though I always wanted to do better.

I attended college for a single year following high school but had no interest in my studies. I dropped out as a C+ student and then took a few interesting life detours before going back to college two years later. When I did return to school, I discovered a few tricks that helped me go from zero to hero in my academics.

I finished approximately three and a half years of coursework in the next two and a half years. Along the way to my bachelor’s degree, I received 11 A+s, while the remainder of my grades were straight As. The A+ grades were in courses in which every one of my test scores was perfect. My performance was so superior to that of everyone else doing A work that the professors took the unusual step of giving me recognition with a grade that was higher than that given to the rest of the A students in the course. This had never been done before at my college.

After I received my degree, I matriculated into medical school, where I scored at the very top of my class on every single exam during my four years. I went on to do a residency in radiology at Duke University and was permitted to skip the clinical internship year. This saved a year of training. I was appointed a chief resident in my final year at Duke.

What changed in my approach to learning after I returned to college? How can I explain how I went from being a lifelong struggling student to an academic star? I have reflected on this a lot over the years.

I want to teach you the same strategies that I used to turn myself from an average student to the best student that I have ever known. The story is instructive, because I’m not the smartest person you’ll ever meet, and because I used study strategies that are backed by a number of evidence-based cognitive psychology principles. Unfortunately, even though there is a lot of useful evidence-based research on what works and what doesn’t in helping students and learners achieve success, very few students (or teachers) have learned how to learn and don’t utilize the best practices when studying.

Using Time Management as a Competitive Advantage

Time management skills are a critical asset, but most students lack sufficient mastery of them. School is broken up into units of time: classroom hours, time until the next major exam or due dates for the submission of papers, semesters, trimesters, academic years, and so forth. If you step back and look at an academic period such as a semester, there are a limited number of hours you have at your disposal to nail the mission of learning the subject matter and successfully completing your coursework.

During this finite time, you can receive huge rewards by investing your time in activities that are highly efficient and effective. Efficient activities are those that produce the maximum amount of learning for the least investment in time and effort. Effective activities are those that produce real and lasting learning.

The goal for each semester is to achieve as much real learning as possible. If you maximize your learning, your grades will take care of themselves. But real learning means that you get to walk away from the semester with durable knowledge that can be used as a foundation for future learning and contributes to you becoming a polymath.

Your long-range goal should be to have a deep, broad, and persistent knowledge base. Having this will fuel your ability to be creative and able to reinvent yourself throughout your life. So if your goal has merely been to log a series of A’s on your transcript, and you’re content to forget what you’ve learned shortly after each final exam, you’ve missed the real point of getting a higher education. If you’re interested in more, let’s examine a few time management hacks I have used that are counterintuitive but super powerful.

Don’t attend class if it isn’t necessary

There are many classes for which attendance is required by the professor. It is either factored into the calculation of your grade, or there is no other way to get your hands on the lecture content. But attending classes is highly inefficient. Besides the time spent in class, this activity involves travel time, even if you live on campus. The time spent sitting in the classroom is out of your control. The professor controls the speed of knowledge transfer. Wouldn’t you like to play the lectures at 1.2X speed or more?

When you walk out of each class, you leave with your set of notes. But you haven’t accomplished much learning up to that point. If you do nothing else but attend class and take notes, could you get an A in the course with zero studying outside of the classroom? Would you remember the course material a year after the final exam? For 99 percent of students, the answer to these questions is no.

However, I have a dirty little secret. Even though I finished number one in my medical school class, I cut almost every didactic lecture during my time there. Most of my course lectures were held in front of a class of around 200 students. Attendance wasn’t required nor taken, and being present didn’t factor into your grade.

In fact, the student body had a note-taking service in which one student note-taker was assigned to (and paid for) each lecture. These students took notes, including making illustrations of anything that the professor drew on the blackboard. They also tape-recorded the lecture. Their work product was a 99 percent accurate transcript of the lecture, including illustrations.

Twice a week, I would commute to school for an hour and pick up the packet of lecture notes from the past few days. In the end, the vast majority of my classmates studied from the note-service notes just like I did, even though they sat in class and took their own notes as well. I’m sure that many of them would tell you that they needed to attend the lectures and take their own set of notes to facilitate their learning. But I call B.S. I skipped almost every lecture and yet achieved the number one score on every exam. The first step to achieving that feat was the extremely efficient management of my time. I saved six to eight hours every day by skipping class, and I put those hours to far better use than my classmates who sat in class all day.

You may not have the opportunity right now to use the same strategy, but if you do, you should consider it. If your professor shares video recordings of his or her lectures, don’t go to class unless it is a requirement!

Of course, a lot of you may be remote learners, so video recordings of lectures may already be your norm. If you are fortunate enough to be in a flipped classroom situation, you’re already watching didactic lectures outside of school. If you have access to lecture videos but no source of lecture notes, then at least watch the lectures at greater than 1X speed. If the video comes with a transcript, there may even be a case to be made for reading the transcript rather than watching the video.

Whenever possible, read things only once

Reading your class notes, handouts, book chapters, and other learning materials multiple times is one of the most accepted and standard practices of studying. Students also like to highlight passages or create marginalia and repeatedly reread those items. We have convinced ourselves that rereading will somehow force the content indelibly into our memory.

But while rereading does add to learning, the benefits are small, and the time commitment it requires produces a poor return on investment. Rereading is not a useful activity as a learning strategy when you consider its lack of efficiency and effectiveness. The same goes for highlighting.

So what should you do with all the time that you save by not rereading? First and foremost, replace rereading with retrieval practice. I will discuss this topic in more depth later. Second, consume other learning materials, such as books, journal articles, and video lectures from other professors, in place of rereading. Deepen your knowledge by gaining the perspectives of multiple other experts. Your professor and your assigned textbook are not the sole sources of truth on the subject.

When I was in medical school, I used much of the free time I gained by not going to class and not rereading to read several textbooks on each subject. In this way I exposed myself to far more content than my classmates. I also used a powerful technique for assimilating this extra knowledge into my mental models: reflection. I asked myself questions about how and why the same concept was explained differently by different teachers and authors. In some cases, their explanations were incongruent, and I had to do further research to determine the truth. By reflecting on these questions, my knowledge grew deeper.

To remember what you learn, use flashcards, retrieval practice, and spacing

Retrieval practice (RP) is the single most powerful hack that learners can employ. RP is analogous to taking your memory to the gym to build the strength to be able to recall a single fact or concept far into the future. Wouldn’t you like to have that superpower? RP is the most powerful tool that you can use to create long-term, robust recallability of the facts and concepts that you want to remember.

Let me explain what RP looks like. In its ideal form, RP works best when you tackle a question and retrieve the answer from memory unaided. Such open-ended questions are more challenging than multiple-choice or true/false questions, which don’t reveal if you really know the material or just have fluency with the answer. With mere fluency, you recognize the answer when you see it, but you can’t generate the answer without this assistance. The challenge of answering open-ended questions is one of many desirable difficulties that feel bad to students but are actually good if they are serious about learning.

We humans are plagued with a very poor ability to know when we don’t know something. We fool ourselves into a false sense of knowing all the time. That is why we see aberrations like the Dunning-Kruger effect. So one of the challenges of RP is to have quality feedback in order to not be fooled into incorrectly believing that we know something. This is one of the many benefits of using flashcards. When you turn them over, you get to face the reality of the correct answer. For most people, that is sufficient to keep them honest.

Another advantage of flashcards is that we can test ourselves whenever we want and don’t need to depend on others, such as study groups and friends. When I was in med school, I made flashcards for everything that I wanted to remember. Flashcards should be very atomic and should only test a single fact or concept. When using RP, isolate your focus to that nugget of knowledge, just as you would isolate your attention to using as few muscles as possible during specific strength-building exercises in the gym.

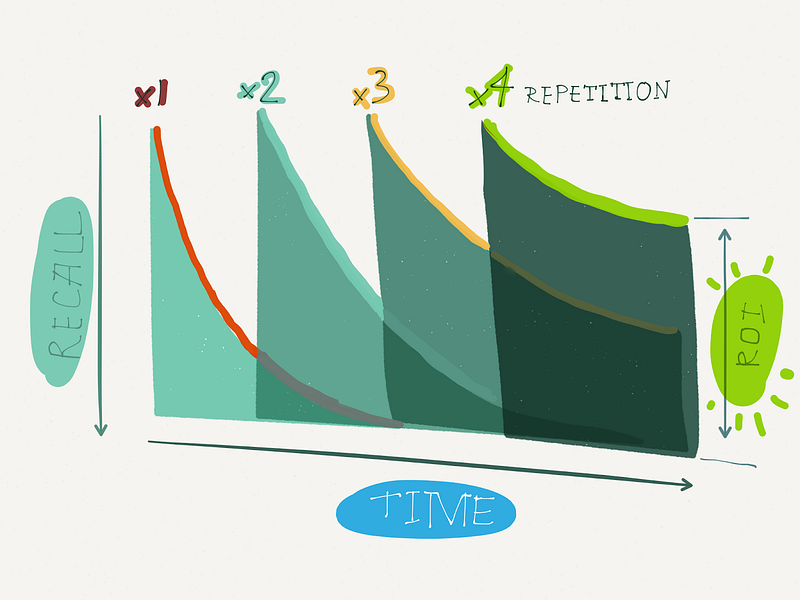

Spacing your RP is the number two most effective study hack for building long-term recallability of the things that you have learned. The antithesis of spacing (“spaced repetition”) is cramming, also known as massing. We all know what cramming is like, and most students believe it’s an effective strategy: pull an all-nighter or save most of your studying for the last few days before a big exam, and you will remember much of the material for the exam.

But while cramming seems to work, it’s kryptonite when it comes to remembering what you’ve learned long term. If your only goal is to get an A on your transcript, maybe cramming feels like a great strategy, but who wants a physician who was a straight-A student but remembers almost nothing from his or her courses? Spacing, on the other hand, has been proven over and over to help build recallability that is far more durable than that achieved through massed studying.

When you use spacing with flashcards, or other varieties of RP, you’re doing the RP repeatedly over time. Imagine, though, that you have 1,000 flashcards. Should you practice retrieval of the answers by going through every one of them each morning? That’s not a sustainable or efficient way to build recall.

The optimal strategy is to study a small subset of your flashcards every day. Roger Craig, a Jeopardy champion, kept a collection of 220,000 flashcards of every answer/question previously asked on the show. Obviously, it would have been impossible for him to practice every card daily or even once every three months. Instead, he used the spaced-repetition flashcard software Anki. Technologies like Anki and my own iDoRecall offer automated solutions for optimally spacing your RP.

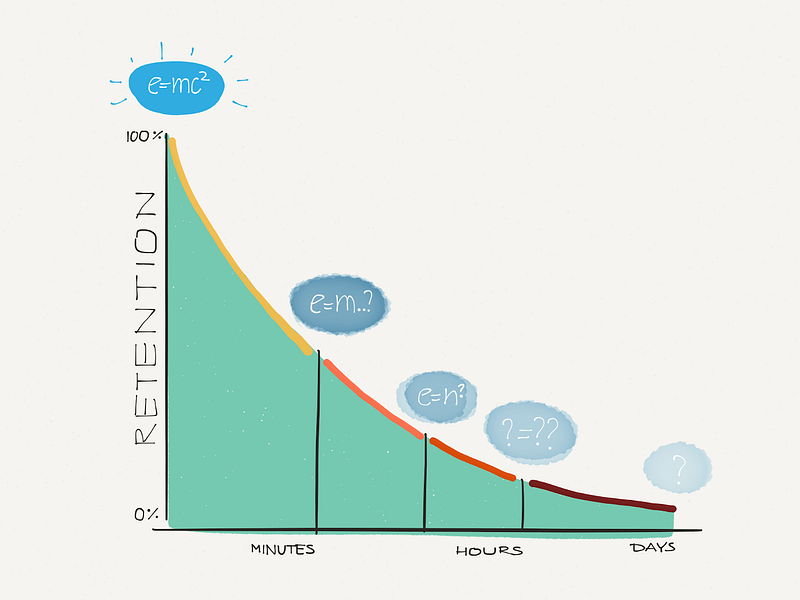

Spacing offers several distinct advantages. First, it offers efficiencies. It makes the use of a massive collection of flashcards a possibility. Second, spacing takes advantage of the forgetting curve. This principle was discovered by Hermann Ebbinghaus in the 1880s when he did research on himself to determine how quickly he forgot nonsense syllables that he had memorized. He discovered that he lost retention of syllables rather rapidly in the minutes, hours, and days after committing them to memory. He concluded that forgetting is a natural trait of human memory that behaves similarly to exponential radioactive decay.

Our natural forgetting curve.

It has been proven that by employing spaced repetition of RP, you can tame the natural forgetting curve tendency and develop long-term recallability of concepts and facts. It has also been shown that RP is most effective when you challenge yourself to retrieve a memory that you are fairly close to forgetting.

This is another desirable difficulty. Think of these as mental exercises, similar to physical exercises, that produce a greater effect when they are more challenging. For example, if you went to the gym and tried to lift a two-pound weight, you would not get the same result as you would if the weight was closer to your maximum capability.

Our recall of information (ROI) quickly fades because of the forgetting curve, but we can overcome this natural tendency with spaced retrieval practice.

So how can a software algorithm know when to show you a flashcard? How can it know when you are fairly close to forgetting something? Of course, it can’t. But a lot has been learned by empirically observing the rate at which people forget and then applying this empirical knowledge.

When I was a medical student in the 1970s, there were no digital flashcard or spaced-repetition automated solutions that I was aware of. It was the dawn of personal computing. My flashcards were paper 3-by-5 index cards, and my spacing algorithm was “practice each card every five days” from the anniversary of the day I created it.

This system worked like a charm. It was neither maximally efficient nor maximally effective. But it worked fantastically. I likely spent more time studying than anyone else in my class, if for no other reason than I stayed home studying all day while everyone else was commuting and sitting in class. I’m convinced that I still would have been at the top of my class if I had studied an average amount of time and skipped all of the extra reading. I enjoyed huge time savings by reading things once, making flashcards, and employing spaced retrieval practice.

Other Learning Strategies

Interleaving, variation, reflection, generation, and elaboration are learning techniques that are highly effective. I employed all of them regularly during the years of my maximal academic success.

Interleaving

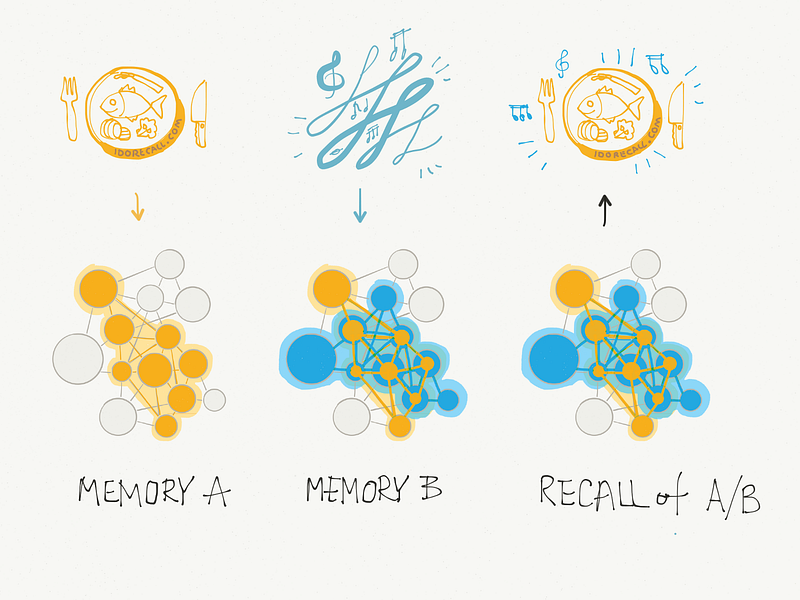

Every time we learn something, we need to attach it to some preexisting knowledge or mental model. Everything we know has some association to something else we have stored in memory. For example, if you think of pizza, you may remember the first date you had with your spouse at a pizzeria or the taste or smell of your favorite pizza.

Our memory is built on an infrastructure of these kinds of associations. We even have some understanding of the neuroscience behind how this works in the brain. The linking that results in memory associations is the result of neural circuits or engrams, a small group of neurons that are capable of storing an individual memory. When adjacent engrams have some neurons in common, the memories that each store can become linked.

Here engram A stores a memory related to a fish meal. Engram B stores a memory of some music that was playing during the meal. B shares some neurons in common with A. Thus those memories are linked. When you think of the meal you might then recall the music and vice versa.

When I was in school, I studied using flashcards that I shuffled to interleave the subjects. By doing so I created many more associations and overlapping engrams between the different concepts and facts that I was learning. This created more pathways through which to retrieve a memory.

When I was in school, I studied using flashcards that I shuffled to interleave the subjects. By doing so I created many more associations and overlapping engrams between the different concepts and facts that I was learning. This created more pathways through which to retrieve a memory.

We are capable of storing more memory in a lifetime than we could ever need before running out of storage capacity. Our problem with the forgetting curve and memory in general is a retrieval problem, not a storage capacity problem.

Variation

Variation is a technique of practice within a subject whereby you change up the practice and learning challenges that you work on in order to gain greater mastery.

A classic example is that if you want to become proficient at three-foot putts in golf, you are better off practicing a mixture of two- and four-foot putts than focusing all of your practice on three-foot putts. As a more academic example, in a subject such as geometry, doing a practice session during which you solve problems in plane, solid, and projective geometry is more effective than focusing 100 percent of a session on a single topic.

Unfortunately, mathematics textbooks typically teach one topic at a time and then assign students practice sets of problems all related to that single topic. When you employ variation, you end up with a much more flexible mind that is able to recognize which formula is the correct one to apply to the challenge at hand. I used the strategy of variation when studying unrelated topics within a given subject in college and medical school.

Reflection

Reflection is a mainstay in academic clinical medicine. The classic example of this practice is the morbidity and mortality conferences held in hospitals, during which doctors sit down and perform a group analysis of what went wrong in a case that had a poor outcome.

By reflecting on the what and why questions and asking themselves individually and collectively how they might approach a similar situation in the future, doctors are better able to learn from their mistakes. Reflection is a fantastic tool for transforming your knowledge into wisdom.

Generation

Generation is a technique of trying to answer a question before you have even acquired the knowledge needed to solve the problem.

Imagine that you know how to calculate the area of a square but haven’t yet learned how to calculate the volume of a cube or any other solid 3D shape. If you were challenged by your teacher to do the latter, you might employ generation in an effort to synthesize the answer. Even if you were not successful, the effort to extrapolate from your existing knowledge base would create some mental infrastructure upon which you could build a mental model of what your teacher was about to teach you.

Physicians constantly use generation because we’re faced every day with clinical scenarios that we’ve never seen before. That’s one of the joys of being a radiologist. There was never a day when I didn’t come home reveling in something new that had challenged me to generate a diagnosis even though I hadn’t had specific prior experience with the set of findings I first encountered.

Elaboration

Elaboration is the ability to express what you’ve learned in your own words and layer it with the related areas of knowledge that you already possess in order to create richer mental models. It’s the underpinning principle of the Feynman technique.

If you can’t distill what you’ve learned into a cohesive story with enough clarity that you could teach it to a novice, then maybe you don’t know it as well as you think you do.

You need to refine your understanding by adding layers of expository details that enrich your mental model and enable you to explain it without notes so that even a fifth-grader can understand it. When it comes to making flashcards, they are most powerful when you create them from memory, in your own words.

Key Takeaways

Excelling at time management is critical to achieving academic success. There are a limited number of productive hours at your disposal in a semester or school year.

I was obsessed with maintaining efficient use of that precious time. I skipped classes when attendance wasn’t required and I could obtain high-quality notes or a transcript of the lecture. This saved me six-plus hours a day in medical school that I could direct toward highly effective learning and deeper study. You may not be able to do this in your current situation, but if you can skip class or can at least watch a recording of the lecture, you should consider the benefits of doing so. There are some disadvantages to skipping, but overall I find it to be a huge net positive when it’s an option.

Read things once to save a lot of time. But as you read, pause and create spaced-repetition flashcards for all of the key concepts and facts that you want to remember. Never create a flashcard for a concept before you fully understand it. Flashcards are for retrieval practice of concepts you already comprehend, and you should employ them to make learned concepts and facts easily recallable. Flashcards are not for learning concepts. If you don’t understand a concept, find a different source, author, scientific paper, webpage, lecture on YouTube, or whatever enables you to successfully grasp the idea. Then make the flashcard.

By cutting down on rereading and making the switch to flashcards, retrieval practice, and spaced repetition, you will build durable recallability of all the facts and concepts that you want to remember.

By using these strategies, you will play the long game of becoming a learned individual. The majority of students may shoot for the A on their transcript, but you will get the A and build a personal knowledge base that you can tap into for years. You can use this deep and broad range of knowledge as a foundation for future learning and problem solving as you encounter unique and novel situations. You will be a more creative person. Creativity is often a concoction born out of the alchemy of mixing seemingly unrelated knowledge to generate new and inventive solutions.

You can further deepen your knowledge by employing reflection, generation, and elaboration so that you can develop numerous and more profound mental models.

I still use these strategies and tactics in my pursuit of lifelong learning. I am convinced that all of us possess the requisite innateabilities to be outstanding students and learners.

Hope you enjoyed reading this;)

“What Do You Think About These Strategies?Please Share your thoughts in the comments below as I learn just as much from you as you do from me!”

Bye for Know,

Sameer

There’s more to that

If you’re looking for more,Please subscribe to my blog by clicking on  Subscribe in a reader the icon or Subscribe via Email by submitting your email id on the side bar ;)

Subscribe in a reader the icon or Subscribe via Email by submitting your email id on the side bar ;)

Amazing,Power,Brain,Memory,Top,Student,Learning,Development,

Improvement,Self,optimize

Amazing,Power,Brain,Memory,Top,Student,Learning,Development,

Improvement,Self,optimize